April 22, 2015 | Posted in DOCUMENTARY, LIVE MUSIC, ORCHESTRAL MUSIC | By from the archives

This review is courtesy guest contributor Conroy Jett, who attended both the Gamelan D’Drum performance in February 2011 and also the “Dare to Drum” film premiere in Dallas, Texas on April 16, 2015.

This review is courtesy guest contributor Conroy Jett, who attended both the Gamelan D’Drum performance in February 2011 and also the “Dare to Drum” film premiere in Dallas, Texas on April 16, 2015.

When Stewart Copeland first formed the Police, “Stewart decided to form a new band fashioned on the vibe and energy of punk music,” according to a blurb from the bio on his official website. Stewart has approached virtually every project since with that same sensibility. Pushing the boundaries has served him well over the years since the Police parted ways, tackling a variety of projects that no rock star drummer would have even considered 25-30 years ago without browning their trousers such as ballets, concertos, operas and commiserating with Pygmies.

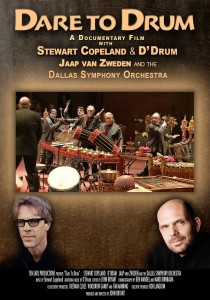

This punk attitude has in turn rubbed off on others with whom Stewart has collaborated throughout this period, including John Bryant, a member of the Dallas, Texas based percussion ensemble D’Drum. They commissioned Stewart to compose a percussion concerto entitled “Gamelan D’Drum” which premiered in Dallas with the Dallas Symphony Orchestra (DSO) on February 5, 2011. Bryant is also the writer, director, producer, sound mixer, etc. of the documentary “Dare to Drum” which premiered at the Dallas International Film Festival on April 16, 2015. “Dare to Drum” tells the epic story of the origins of “Gamelan D’Drum” and the struggles it faced to finally become reality.

Copeland and Bryant’s unconventional punk attitude can been seen—though not apparent at first—in the scene containing fire near the beginning of “Dare to Drum” which describes the challenge of the project that would become “Gamelan D’Drum.” The fire symbolism provides a contrast to the concerto’s premiere, which was delayed and nearly derailed by a freak winter storm that paralyzed Dallas for several days in February 2011. In a Q&A after the “Dare to Drum” premiere, Bryant said the decision to juxtapose the scene with fire was to show defiance to the storm that would become the biggest obstacle the project faced.

The symbolism of fire returns again later in the film, even more defiantly in the footage of the D’Drum ensemble and conductor Jaap Van Zweden preparing to take stage when the premiere finally comes to reality in spectacular form. Ironic humor permeates the film, including a scene where D’Drum rehearse with the full orchestra. Stewart, known for being a bombastic performer on the stage, has to tell D’Drum to tone down the noise a bit as they are drowning out the orchestra.

Another aspect of the film that features the punk attitude takes place during a scene in which D’Drum and Stewart meet to play the live to a synthesized recording of the orchestra. Ron Snider, considered the closest thing the band has to a band leader, adds a glissando to the piece that was not part of Stewart’s composition. Stewart finds the playful addition a good fit to the work and allows it to become part of the final version. In fact, it is such a perfect fit to Stewart’s style of composition that after one has heard the finished product, it is hard to imagine the piece without the glissando.

Stewart Copeland at the “Dare to Drum” film premiere, April 16, 2015 in Dallas Texas. Photograph courtesy Conroy Jett.

Fortunately, it is the playful banter between Stewart and the various members of D’Drum that dominates the the majority of the film. This includes many touching and humorous moments as the various members involved with this project discuss its history and all the amazing things that happened to make the project a reality. The origins of the D’Drum ensemble is quickly related; they have been jamming every Monday evening since the early 90‘s, and then the various members of D’Drum talk about how they got into drumming. One of the most memorable examples comes from Ed Smith who says it was the now 51 year old performance of the Beatles on Ed Sullivan that made him decide to become a drummer—he wanted to make girls scream. Then, the ensemble discuss how they commissioned Stewart to take on the project. They all agree that no one but Stewart was qualified for this project with his unique pedigree of world music background, an early introduction into Gamelan music through his college roommate, and his subsequent forays into classical music post-Police. Most amusing of the responses from the members, when hearing that Stewart Copeland has agreed to compose this piece, is from Doug Howard who asks: “Who is Stewart Copeland?”

Another area where “Dare to Drum” focuses is the brotherhood that exists among the members of the drumming community, which should be no surprise to anyone who is a drummer or has been close to one. The film stresses how they speak their own language and that is an important theme for the film. This project is essentially taking different drumming languages (the unbridled language of the Bali gamelan world where no two villages have their gamelans tuned to the same pitch) and creating a new drumming language by having gamelans specially made that are tuned to concert pitch and to be performed with a western orchestra. The film documents Ed and Ron’s journeys to Indonesia and shows their gamelan makers creating these custom gamelans for “Gamelan D’Drum”.

The first hint of drama in the film comes when two of the members of the ensemble, who are also members of the DSO, learn that the maestro himself Jaap Van Zweden is going to conduct the concerto. They show a bit of nervousness at first because they know all too well of the maestro’s high expectations.

Just as it seems like everything is going well, what is now an infamous snow storm coincides with both the Gamelan D’Drum premiere and the 2011 Super Bowl. The storm drops in on Dallas like an unwanted guest and brings the city, not used to this extreme winter weather, to its knees. They are only able to squeeze in one day of rehearsals with the orchestra, in-between the multi-day storms, and have to cancel the first two performances. One memorable scene shows the D’Drum members making their way to the Myerson Symphony Center on the day that should have been the world premiere but it is hauntingly empty due to the canceled rehearsal. David Kim’s moving violin solo from the premiere serves as a fitting soundtrack to these despondent moments.

Another blow is delivered to the premiere on Friday, when a forecasted half-inch of snow winds up becoming six inches on top of the ice and snow that had fallen during the days prior. On Saturday, with snow still on the ground, they decide to proceed with the premiere. However they only get a partial rehearsal because there is another piece to perform, Mendelssohn’s Scottish Symphony, which the orchestra has yet to rehearse.

In the end, despite the Grand Guignol that the project has become, the feisty fire for music within their bellies takes hold and the premiere comes off without a hitch. After the conclusion of the concerto, the audience delivers one of the longest and most memorable ovations the DSO has ever seen.

It would not be surprising if a century from now, people talk about “Gamelan D’Drum” with its groundbreaking and memorable premiere much like we talk about the infamous premiere Igor Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring”, with the extraordinary ovation of this premiere a counterpoint to the riot that accompanied the premiere of Stravinsky’s work. The presentation of that Herculean story in this wonderful documentary should go a long way to cementing the legendary status of the Gamelan D’Drum premiere four years ago.

Related articles across the web

Related posts at Spacial Anomaly

from the archives

"from the archives" is our Spacial Anomaly account for guest blogger posts, as well as for sharing and re-publishing of articles on fandom and fan history which are no longer available elsewhere online. Such articles are published here on Spacial Anomaly with full permission of their original authors. Please contact us if you are interested in submitting a guest post, or have any writings on fandom history, culture and meta you would like to see archived at Spacial Anomaly. Better still, consider joining our writing staff directly!

Leave a Reply

*

Be the first to comment.